SHEPARD FAIREY INTERVIEW (Full Length Edit)

SHEPARD FAIREY STUDIO VISIT (Full Length Edit)

Products

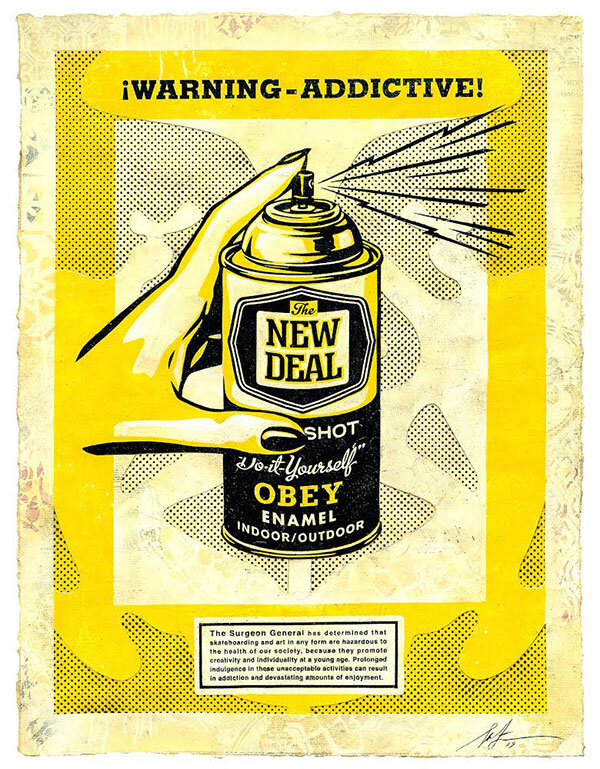

NEW DEAL x SHEPARD FAIREY Artist Edition “Warning Addictive” Limited Edition Skate Deck, 2020

8 ⅝ x 31 ⅝ Inches

Screenprint on 7-ply dyed hard maple.

Numbered edition of 400 with 14 Artist Proofs.

Accompanied by a numbered Certificate of Authenticity from New Deal Skateboards.

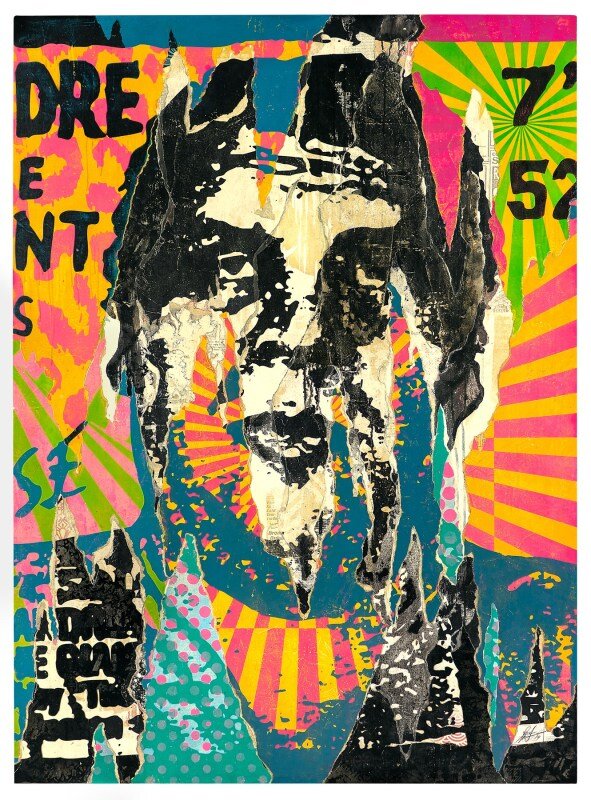

NEW DEAL x SHEPARD FAIREY Artist Edition “Warning Addictive” Limited Edition Art Print, 2020

18 x 24 inches

Screen print on thick white Speckletone paper.

Signed by Shepard Fairey.

Numbered edition of 250.

Many of the first WARNING ADDICTIVE prints from 2019 were destroyed by the fire that took Andy Howell’s house in 2019 shortly after the New Deal 1990 Exhibition at Shepard’s Subliminal Projects gallery. Referencing the original painting, the artist created a new print for the launch of the New Deal collaboration in 2020. ““It’s very ‘Meta,’ the fine art piece (from 2019). I decided I could make a new print separating that into a screen print. Now it’s got the signature from the original art from 2019, and then it’s signed again in pencil for 2020. I like the life cycle story there. “It’s very similar to what I would do on the street. I’d put a poster up, and then somebody would rip at it, and sometimes I would photograph it, and turn the ripped poster into a print, and put that back out on the street, again.” ~ Shepard Fairey, Artist

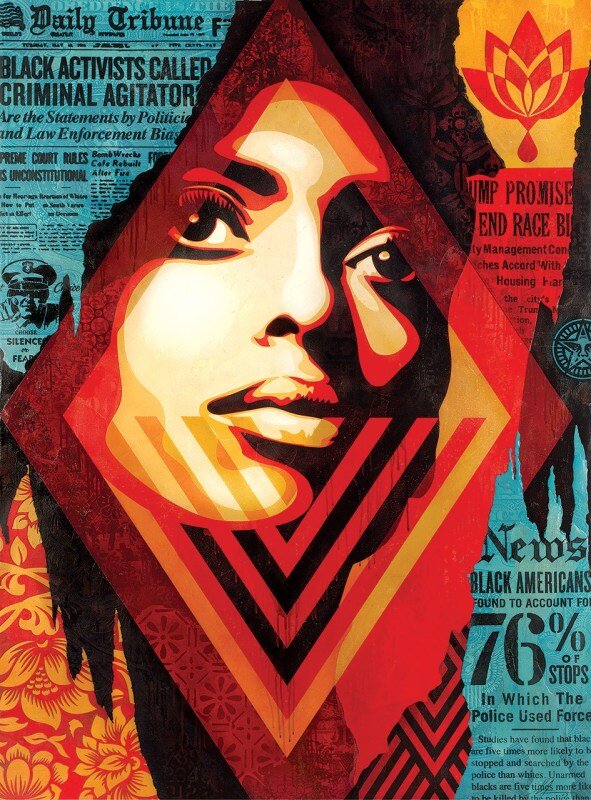

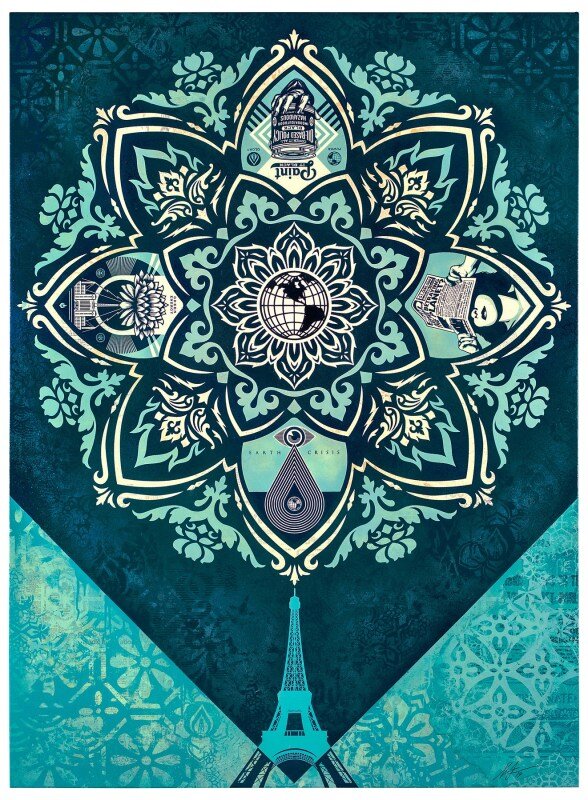

Shepard Fairey Gallery

New Deal 1990 Exhibition

*Artist Interview

Shepard Fairey: I’m Shepard Fairey. We’re in my gallery, Subliminal Projects in Los Angeles, California.

Ted Newsome: Right on. Tell me your New Deal story Shepard.

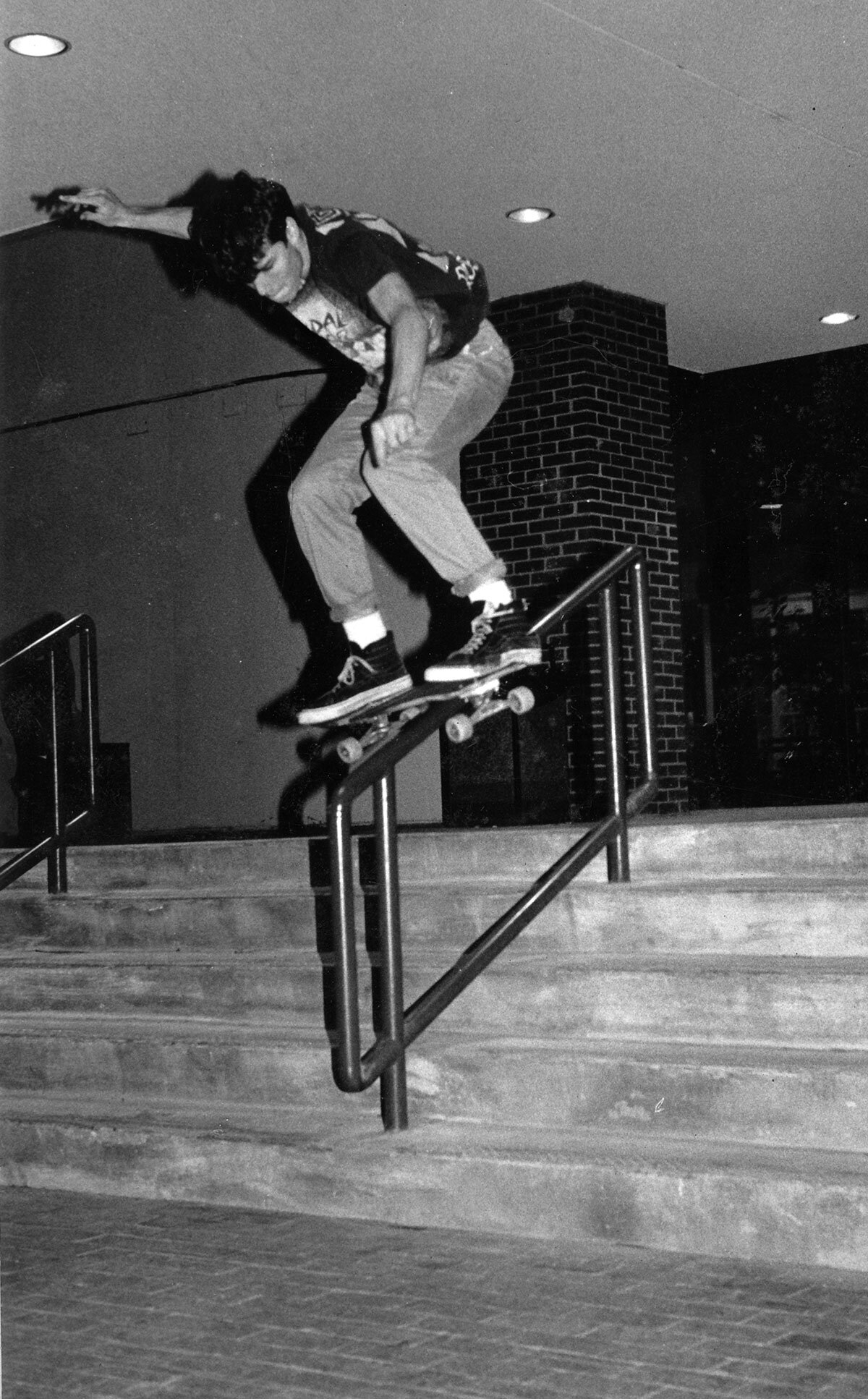

Shepard Fairey: My history with New Deal goes back even further than New Deal. I was a big fan of Schmitt Stix in the late 80s. I started skating in ‘84 and I think it was late ‘87 or early ‘88, I saw some stuff of Andy Howell in one of the magazines. I think the first thing was a wall ride off a jump ramp to board slide. It was really sick, from a contest. Then shortly after that in the spring of ‘88, the Savannah Slamma contests, the second version, was happening and I lived in Charleston, South Carolina: that’s where I’m from. It was a pretty short drive for me and a few of my friends to borrow a station wagon and head down to Savannah.

Ted Newsome: I was there for Savannah Slamma II; that contest was amazing.

Shepard Fairey: I watched Andy skate and I really liked his skateboarding; I started paying close attention to what he was doing. Then I noticed that he had drawn his own board graphic for Schmitt Stix. Then when the launch of New Deal happened, I was very excited because the positioning right out of the gate was New Deal is a skateboarder-run and owned company and knowing that Andy was involved as a creative and a skateboarder, I knew that it would be … let’s say avant guard.

Ted Newsome: How did those early days of New Deal influence you and how did you carry that energy forward?

Shepard Fairey: When New Deal launched, what I thought was really amazing was the writing for a lot of the ads, the team that they assembled, and then the design. The ad campaign was all white, black, and yellow so every ad was easy to recognize as soon as the new magazine came out. I liked the cohesiveness of it in one regard, but then it also addressed each team riders’ unique personality within the content of the ad. To have the continuity with the variation, I thought was really smart. It all had an attitude of sort of poking fun at the establishment, whether that was the broader square establishment or even the establishment within the skateboard industry, but saying, “Hey. We’re a little smarter. We’re a step ahead. We’re subverting the dominant paradigm” ... with a nod and a wink.

Ted Newsome: The ads definitely spoke to skaters in a new way.

Shepard Fairey: It just resonated with me. It was the perfect sensibility for where I was in my life, sort of skeptical of things, but also just liking to have fun. Skateboarding was a perfect outlet for me as a physical thing to just blow off steam, get out aggression, but also as a creative realm. The way in which New Deal embodied all the things I thought were exciting about skateboarding culturally were, well that was awesome. Then also the way that New Deal was pushing forward on street skating, because street skating had been sort of seen as what you did when the ramp was wet or the park got shut down. Yet, it was the most democratic area within skateboarding and I loved street skating.

Ted Newsome: Street skating was a new frontier.

Shepard Fairey: I love ramp skating too, but street skating is a way of once again, subverting the urban landscape and being creative with it in ways that people totally shouldn’t be. I love the rebellious side of it, the democratic side of it, and for a company to be really embracing that, New Deal was at the leading edge. There were so many different things about the way things were communicated and the way the videos weren’t ... Useless Wooden Toys, what a great name to take what’s usually a disparaging commentary and turn it around and embrace it and say, “Yeah. Well, look at what we’re doing with these useless wooden toys.” Then there was the Surgeon General’s warning, which I addressed in my piece, “skateboarding is dangerous because it promotes creativity at a young age.” The idea that everyone else is just a slave to the status quo or to conformity, but people who can think for themselves and create for themselves are such a threat. That was right up my alley.

Ted Newsome:: I love that. Okay, talk a little bit more about Andy Howell.

Shepard Fairey: It’s probably kind of embarrassing or sycophantic for me to say, but I mean, I was just in awe of Andy Howell. He was a hero of mine. He was someone who was good at skateboarding, was good at art, had developed his own brand with New Deal and went on to develop several other really cool brands, Underworld Element, which became

Element, Zero Sophisto, which became Sophisto. The reason I’m in California is because Andy asked me to come out to California to work with him on Sophisto and collaborate with him. He also offered to help to support financially what I was doing with my work, with all the Obey Giant stuff. Yeah. Andy was somebody with a vision for how his own art would manifest within the culture that he cared about, that I emulated. I think it’s safe to say that I wouldn’t be where I am, if Andy, as a role model, hadn’t been there both as someone to look up to and someone to actually collaborate with.

Ted Newsome: Let’s talk about the 30th anniversary art show coming to your gallery. How did it feel to come full circle?

Shepard Fairey: The New Deal 30th anniversary art show, I think it was a great concept because there’s so many artists who were impacted by New Deal, who now have successful art careers. When the great thing about New Deal was when it launched, it was saying, “Hey, the art side is really, really crucial.” That was something that had always been important within skateboarding, but somehow was sort of relegated to behind the curtain in a sense. Now being an artist within skateboarding is cool, you’re out front about that. To take the evolution of the culture that really New Deal was pushing from 30 years ago and look at where a lot of these artists are now, as well as younger artists who maybe the ripple effect is two generations deep, but they still were feeling the effects of what New Deal did.

Ted Newsome: It was wild to hear all the stories of New Deal’s influence through the art show.

Shepard Fairey: It’s pretty amazing. This gallery, Subliminal Projects, was really a product of Andy Howell’s interview in Transworld in 1991, I think it was. His Pro Spotlight where he said, “Skateboarders aren’t getting enough credit for the art they’re making so I’m going to work on a book. If you are an artist that skates, send me some stuff.” That book, I guess, eventually happened as Aaron Rose’s Dysfunctional book, right? I connected with Andy, we talked a lot about the value of art within skateboarding. Then later on my friend, Blaze Blouin, and our other friend Alfred Hawkins, we decided we were going to make a skate brand where instead of having pro skateboarders for the models, that it was going to be an artist designing and having their name on the model.

Ted Newsome: Ah yes, that board company was called Sublminial, right?

Shepard Fairey: Yeah, Subliminal, the board company, failed miserably because in 1995/1996, people were not really ready for that; I like to think that it was predictive. Later on, when we started this gallery in Los Angeles, I wanted to revive that name because this gallery is all about an intersection of skateboard culture, street culture, and fine art. However, you describe that, but this mix of high and low is what we want to cover here in the gallery. I think this show is obviously a perfect embodiment of the whole mission of Subliminal Projects.

Ted Newsome: Can you speak to your New Deal 30th piece specifically? You mentioned the surgeon general’s warning.

Shepard Fairey: Yeah, I got plenty to say about this piece. I went to RISD, I can bullshit my way through an art talk! This piece was inspired by the early New Deal advertisements, which used black, white, and yellow. Everything had a spot yellow, which was very recognizable. One of the icons for New Deal was a spray can ... there was also this Surgeon General’s warning which I slightly re-worked: “The surgeon general has determined that skateboarding and art in any form are hazardous to the health of our society because they promote creativity and individuality at a young age. Prolonged indulgence in these unacceptable activities can result in addiction and devastating amounts of enjoyment.” That, for me is kind of an encapsulation of the way skateboarders take things and subvert them and in a witty, smart way. I always loved what Andy did with that.

Shepard Fairey:

I was trying to find the perfect hybrid of my sensibility with my Obey Icon face, with New Deal. I do a lot of illustrations using a spray can because a spray can is a tool that is essential to my art. Where there was overlap between what Andy had done for New Deal and what I do with my own work. I wanted to marry the two and yeah, this is an actual cut stencil that’s glued down. The dots are a reference to Zip-a-Tone, which before everybody used the computer for ads, you had to actually put the tone down ... and all old tech stuff that you can Google. Anyway, I knew Andy would know what I was talking about and would appreciate it.

Shepard Fairey: It’s just a tribute to that moment in skateboarding and how much it meant for me. I wouldn’t have

potentially used the spot colors I use in my work, red, black, and white, if I hadn’t been inspired by both New Deal and then things like Russian constructivism and Barbara Kruger’s work, but for sure New Deal was a big part of that limited color palette, make your low budget turn into an asset rather than a liability. Keep it simple.

Ted Newsome: You have since laid a lot of creative history with Andy Howell, do any early stories come to mind?

Shepard Fairey: Andy Howell and I collaborated on several things, one thing that comes to mind is a video premiere in New York City. Andy had made a video with you, Ted, “The Freedom Video” which was a Sophisto and REN video. It was great, really awesome riders; Jamie Thomas, a bunch of different people, Laban

[Pheidias]. I had made a video called Attention Deficit Disorder. Well, actually it was called Attention Deficiency Disorder. Now I know the right way to say it, but yeah, back then no internet. We were all talking like, “Yeah. It’s called attention deficiency disorder.” Close, but not quite, but anyway, we had become friends with Aaron Rose from the Alleged Gallery in New York City. I was spending a lot of time in New York City, putting up stencils and stickers and posters.

Ted Newsome: New York is a playground for getting up.

Shepard Fairey: People ask me all the time like, “Oh, you must’ve loved graffiti; that must be where your bombing mentality came from.” No. My bombing mentality came from skateboarding because all the skateboard companies promoted with stickers. I loved graffiti as well, but really that was already ingrained in me from the D.I.Y. side of skateboarding. Skateboarders have always had that, it’s us versus the world and we’re going to get over so Stickering makes perfect sense. I had done a lot of stuff in New York on the streets. What Alleged was doing was showing things having to do with skateboard culture and street culture and music culture. It was great for me to get to premiere my video along with you and Andy, the Sophisto/REN Video, because that gave me credibility.

Ted Newsome: That’s rad, I remember that A.D.D. video.

Shepard Fairey: I was no one. To get to be the opening act with Sophisto was a big deal. I remember rendering the video because it was done digitally — It was one of the first digitally done skateboard videos. We finished editing the video the night before and hit the button for it to render and it said it was going to take 36 hours. It’s like, “We’re going to miss the premiere!” It finished rendering two hours before the premiere was supposed to happen. I drove 90 miles an hour from Providence to New York City and when we’re getting close to the gallery, there was a traffic jam. I was like, “What the fuck is going on?” Then I realized it’s all the people flooded in the street from the gallery blocking traffic. Cars can’t get by because the video was showing in the front window. Right as the Sophisto video ended, I was handing off my video to Aaron Rose. It was probably the most stressful day ever for me. I was like, “I’ve been given a shot and I’m going to blow it,” but it all worked out.

Ted Newsome: Yes, yes, you did the opposite of blow it. Thank you so much, Shepard.

Shepard Fairey: Sure, any time.